It Always Begins On Reddit

Per usual, my latest journey down the internet rabbit-hole started on Reddit. I frequent the r/climatechange subreddit and stumbled across this thread on climate change solutions. In it, I found extensive discussion of population control methods. The least controversial method that I read concerns urbanization.

I’ve read a lot about urbanization as a method of population control, but my gut-feeling was that promoting urbanization is a double-edged sword. While it makes sense that urbanization in countries can stymie rural population—the population that is often the most poverty-stricken—I wondered if greater urbanization decreases poverty in aggregate.

For example, if a rural family in Ghana moves to Accra then they are likely to have fewer children. But if they are stuck in a slum in the outskirts of the city, are their lives improved enough to justify the move? Is overall welfare improved, or are there just fewer people in poverty? Isn’t overall welfare really what’s important, and not just population control for its own sake?

What Does the World Bank Say

I decided to investigate links between urbanity and poverty reduction. The World Bank provides great data on a range of development topics, so I downloaded several datasets broken out by country. I downloaded one on the urban population measured as a percentage of total population. I downloaded another on the poverty headcount measured as a percentage of the population living at $1.90 a day. I also took measures on total population and gdp per capita. You can find a full excel workbook with each tab devoted to a different World Bank dataset here.

Before diving into the data, let’s get a broad understanding of the trends in poverty reduction and urbanization overall. Here is a World Bank plot on poverty reduction:

It’s worth stepping back and trying to grasp how remarkable this is. In 1981, 42.1% of the world’s population lived in poverty. In 1990, 35% of people lived in poverty and in 1999 28.6%. The final year for which there are data is 2015, where the rate is 9.9%. In other words, around 1980 2 out of every 5 people lived in poverty whereas today 1 out of every 10 people live in poverty.

This is stunning. I don’t want to sound too high-minded, but it’s worth noting this the next time we think the world is crumbling. In the Western world we are attuned to what’s happening to other Western nations, so we too often think the world is tearing at the seams. Yet, if we broaden our outlook, the lives of people who are in the most dire of circumstances are improving at an impressive rate. This is something to be applauded—and expedited. Okay I’ll get off my soapbox.

Here is the World Bank on urbanization:

In contrast, the rate of increase for global urbanization is more linear. In 1990, the urban population was 42% of the total global population while in 2000 this rate was 46% and in 2010 51%. In 2018, this rate was 55%.

It’s evident that these two measures are inversely related. But to what extent are they inversely correlated across countries? Using the 2018 data for urbanization and the 2010 data for poverty (since it has the most data) I get their correlation:

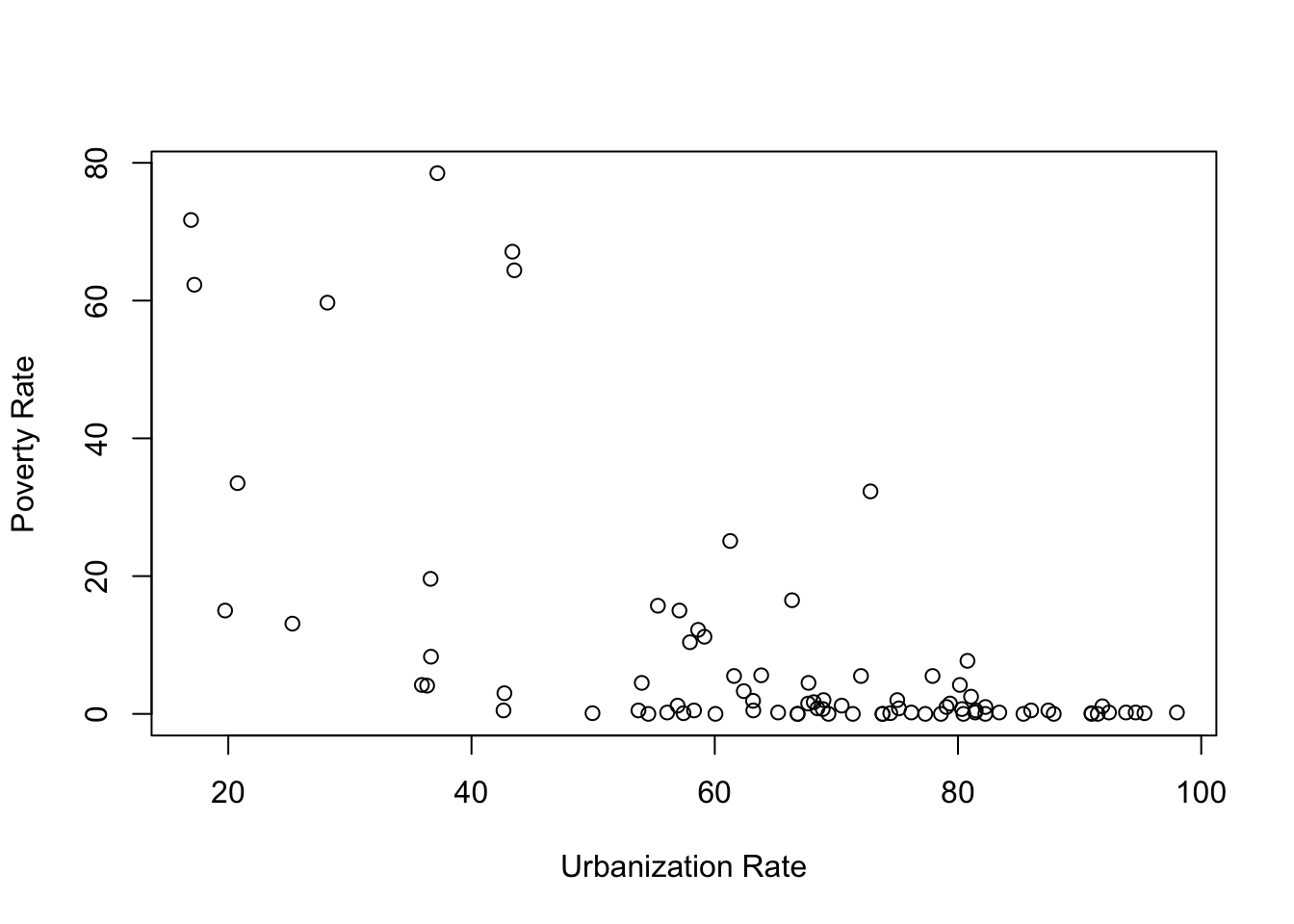

cor(final$urban_pop,final$poverty_rate)## [1] -0.6100478The correlation is about -.61, indicating a strong negative correlation. However, while this gives a sense of how the two variables move in aggregate, it doesn’t give us a general idea of the shape of the curve. A quick plot helps do the job:

plot(final$urban_pop,final$poverty_rate,

xlab = "Urbanization Rate",

ylab = "Poverty Rate")

We see that the relationship is not quite linear, so if we want to create a line of best fit for the graph then we need to fit a higher-order (polynomial) regression to the data. I do that here:

reg = lm(poverty_rate ~ poly(urban_pop,2), data = final)

summary(reg)##

## Call:

## lm(formula = poverty_rate ~ poly(urban_pop, 2), data = final)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -30.178 -4.175 -0.913 0.482 53.793

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 8.531 1.470 5.804 1.22e-07 ***

## poly(urban_pop, 2)1 -99.095 13.472 -7.355 1.38e-10 ***

## poly(urban_pop, 2)2 43.179 13.472 3.205 0.00193 **

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 13.47 on 81 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.4428, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4291

## F-statistic: 32.19 on 2 and 81 DF, p-value: 5.163e-11I now want to see the important outliers, i.e. populous countries which have high poverty and low urbanization. I’m motivated by this tweet, which claims that Ethiopia has a surprisingly low urban population for a populous country:

I learned this months ago, and I still can't get over it: Ethiopia has a population of a bit over 100 million, and its second largest city has fewer than 500,000 people (I think it's Mekelle, but statistics seem to be fuzzy)

— Market Urbanism (@MarketUrbanism) August 5, 2019

Urbanization and Poverty

To better understand the negative correlation between increasing urbanization and poverty reduction, while taking into account gdp per capita and population size, I create the following plot:

ggp = ggplot(final,aes(x = urban_pop,y = poverty_rate,color = income_type,text = `Country Name`, group = 1)) +

geom_point(aes(size = total_population), alpha = 0.5) +

geom_line(color='red', aes(y = poverty_rate_pred), size=1, alpha=0.4) +

scale_size(range = c(1,14)) +

scale_color_brewer(palette="Dark2") +

bbc_style_new() +

theme(

plot.title = element_text(hjust = 0.5),

plot.subtitle = element_text(hjust = 0.5),

legend.position = "top",

legend.justification = "top",

axis.text=element_text(size=10,face = "bold")) +

labs(title="Urbanization and Poverty",

subtitle = "Insider Revenue is an Increasingly Large Component of Total Revenue") +

xlab("Urban Population (% of Total Population)") +

ylab("Poverty Rate (% of Total Population)")

ggplotly(ggp,

tooltip=c("Country Name","urban_pop","poverty_rate","total_population")) Here I plot urbanization and poverty rates as before. The size of the bubble is the total population of a country and the color of the bubble is the income level based on gdp per capita. The red line is the line of fit I create using the weights from the polynomial regression. The plot is interactive so feel free to hover over the dots.

Right away we see that high income countries are generally grouped at the bottom and to the right. Most rich countries have been urbanizing for several centuries now. It’s no surprise that large Western nations (Canada, the UK, the US to name a few) all have >80% urban populations and low poverty rates. The least urbanized high income countries are Slovenia and Slovakia. It is interesting to note that middle and high income countries in Eastern Europe have much smaller urban populations than other Western countries but also have extremely low poverty rates—lower than in Western countries.

Middle income countries are not as clustered together. There are several Latin American countries such as Colombia, Peru and Mexico that have high urbanization rates but poverty rates generally higher than those of Western countries. An interesting case is Indonesia. It is both highly populous with about 267M people, but has an urban population rate of only 55% and a poverty rate of 15%. It is similar to China in this way, though China is of course much more populous.

There are notable outliers. In support of the above tweet, Ethiopia has a very low urbanization rate (~20%) and a high poverty rate (~33%). What makes it such an important outlier is that it is also very populous—it has 109M people, the second most in Africa. Similarly, Bangladesh has even more people (~160M), a low urbanization rate (~36%) and a high poverty rate (~20%).

There are countries that buck the trend in a different way. Someone replied to the above tweet that Thailand’s largest cities are small compared to its population. This plot bears that out. In a country of about 70M, Thailand’s urbanization rate is 50%. However, despite low urbanization its poverty rate is very low at .1%.

Why We See What We Do

So there appears to be a relatively strong correlation between poverty reduction and urbanization. Why? What about moving to the city improves people’s lives? There is of course an extensive literature on this topic and the following reasons are not exhaustive.

In general, people have greater access to more productive work in cities. What does this mean? In simple economic terms, it refers to work that contributes more to GDP. Not only do people contribute more to the economy in the cities, but they receive higher wages for this work.

In addition to higher wages, people have greater potential to increase their human capital. Generally, people have better access to good education in cities and outside of rural areas. People are able to learn new skills, acquire new trades and in turn reap the rewards of larger wages in return for their skilled work.

Further, service systems in cities are more improved than in rural areas. Better access to good transportation infrastructure and greater access to healthcare contribute to the improvement of urbanites’ lives.

Aside from the benefits of moving to a city, there are knock-on benefits to leaving rural areas. In general, work in rural areas (i.e. farm work) is not as productive as those in urban areas and people receive low wages. In many countries, to compensate for low wages families have more children to (among other reasons) help run farms and earn wages for the family. After urbanization, not only is there less space for large families but families also lose the incentive to have more children. This is because it is more costly to live in cities and because the “return on investment” of having another child is not as high in rural area—in part because individuals are able to earn higher wages themselves.

It’s impossible to talk about the benefits of urbanization without mentioning China. China enacted what some call the greatest ever anti-poverty campaign by making it easier than ever for people to move. People took advantage of this opportunity and moved in troves to urban areas. Between 1981 and 2011, the number of Chinese people living in absolute poverty declined by 753 million people.† This accounts for 50% of the total world decline in poverty during this time. In 1981, the urban Chinese population was 20.1%. In 2011, it was about 50.5%.

Urbanization and Economic Growth

So if poverty reduction and urbanization are linked, then there must in turn be a correlation between urbanization and economic growth—right? Yes and no. A correlation exists but is lower (in absolute value) than that between poverty and urbanization.

cor(final$urban_pop,final$gdp_per_capita)## [1] 0.5350263There is great debate on why this is the case. One of the best investigations of this phenomenon that I found comes from Remi Jedwab, an economics professor from my alma-mater. In a paper he co-authored called Urbanization without Growth, the authors argue that there are two distinct phases of urbanization.

From 1500 to around 1950, urbanization increased drastically only for the richest nations. However, before widespread industrialization in the West economic growth was not always commensurate with urbanization. The relationship between urbanization and growth is strong only when looking at the early 20th century after the industrialization of the US and Western Europe. If we were to take this correlation using data only from the 19th and 20th centuries, presumably we would find a stronger relationship.

However, in the late 20th century this relationship reversed. Rapid urbanization occurred in predominantly less developed countries. As some of the largest cities are now in countries with lower economic development, urban population is less indicative of both urban and nation-wide living standards. The authors that argue that urbanization in poorer countries is a new development, but urbanization without growth is not.

This observation has interesting implications. In the West we tend to associate urbanization with industrial expansion and development (à la the Industrial Revolution in Western Europe and the United States in the early 1800s). However, from a historical perspective this view doesn’t hold water. Urban growth rates increased throughout history, but most often without growth like we saw in the Industrial Revolution. Data on current urbanization trends conflict with this view as well. Urban growth is greatest now in less economically developed countries.

What Should We Do?

So what kind of conclusions can we draw with this information? Is urbanization good or bad if economic growth doesn’t always follow?

I think it comes back to the relationship between poverty reduction and urbanization. Even without growth, on the whole human lives improve with greater urbanization. People make more money, families are more financially secure, individuals have greater access to healthcare and resources to improve their human capital, and in general urban mortality rates are lower than rural mortality rates.

We must also accept the fact that even if urbanization isn’t always associated with growth, urban growth has not stopped and it does not seem like it will in the near future. The answer lies in sustainable urbanization. The World Bank devotes a great deal of research towards strategies for “people-oriented” urbanization. These strategies must address environmental concerns and disparities between resources that improve the plight of the urban poor at the expense of the rural poor. Policies that address infrastructure and a proper safety net for those on the brink of poverty are also essential for a sustainable path to urban growth.

These are all reasons as to why urbanization without growth might still be good overall. However, it would be better if urbanization was associated with greater growth. There are many reasons why urbanization doesn’t always entail growth. An important one has to do with the rising costs of urban living. This is a problem that affects both poor and rich nations in many serious ways. I’ll devote a different post to this problem in the future.

†I got this figure on Chinese poverty reduction from the great book China’s Great Migration: How the Poor Built a Prosperous Nation. I highly recommend this book for anyone interested in China specifically or the benefits of migration more generally.