I’m going to cross-pollinate blogs for the first time. I analyzed a dataset for an article I wrote for the Yankee Devil Record on journalist deaths. (What Cheer is not always cheery…). The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) maintains the dataset. It features journalist deaths since 1992.

CPJ only lets you download the dataset for deaths where the motive is known but not for deaths where the motive is unconfirmed. I don’t know why they partition the data in this way. Perhaps many of these killings are under investigation and CPJ can’t collect enough detail.

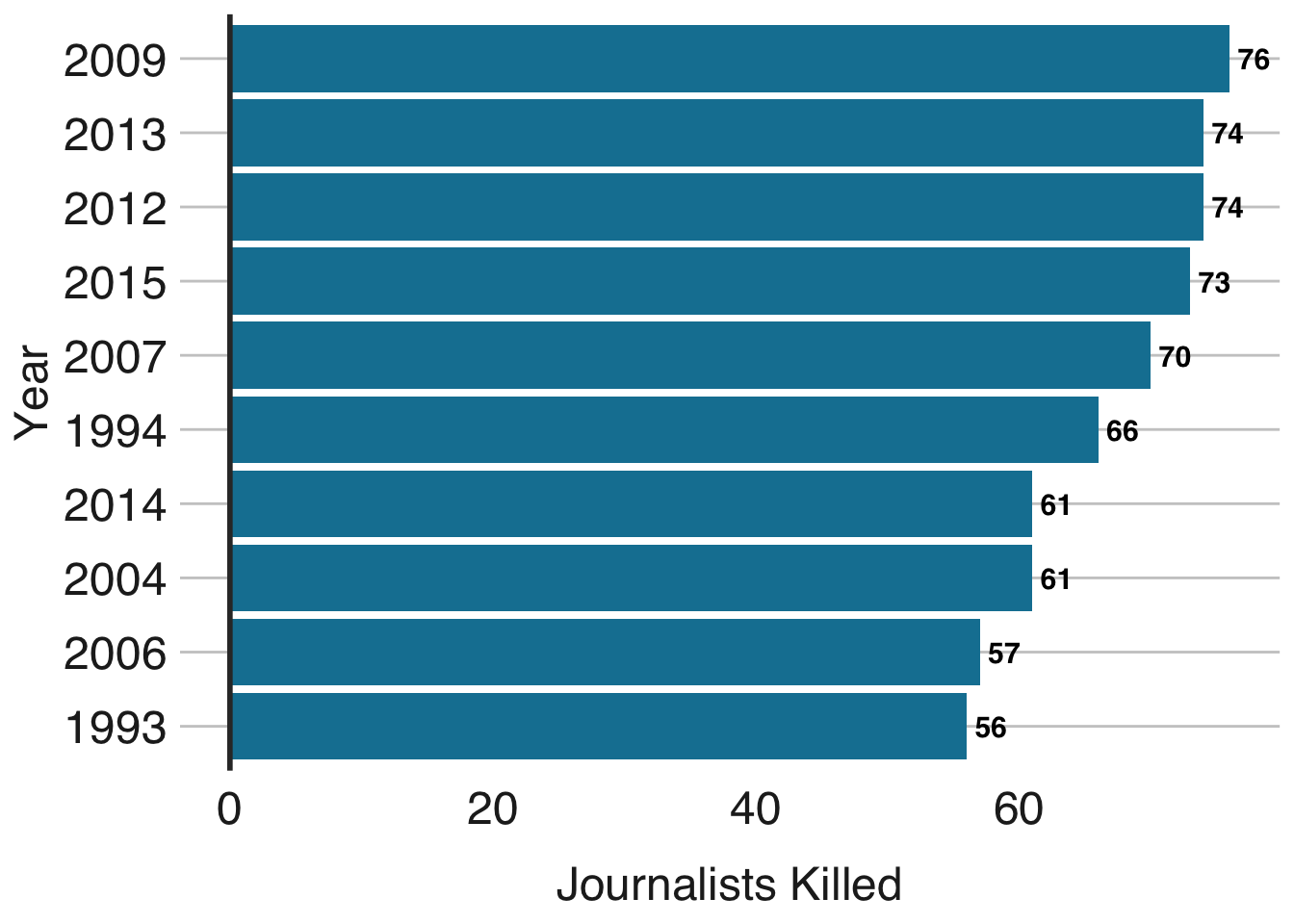

I was most curious about the most deadly years for journalists. I read some recent reports that claim it is more dangerous to be a journalist today than it has been in the past decade. There are several recent years that are among the most deadly:

These are the top 10 deadliest years since ’92. In 2018 there were 54 casualties, in 2017 47 and in 2016 50. These figures aren’t that much lower than those of the top 10 years, but it doesn’t look like there is a stark rise in journalist deaths in recent years either. If anything the graph is a testament to how much more deadly the ’00s and ’10s were than the ’90s for journalists.

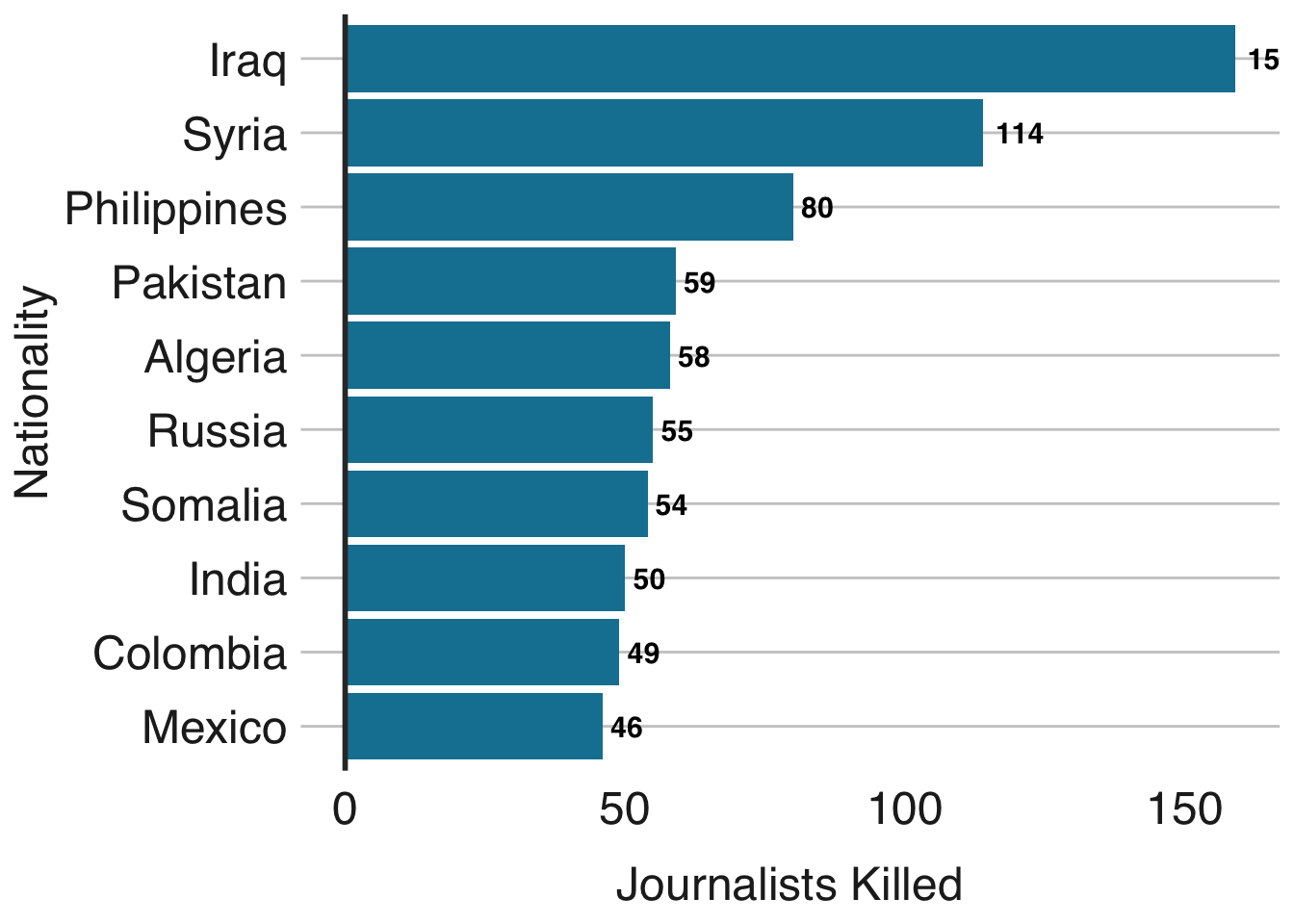

I then took a look at individual countries:

It’s no surprise that Iraq and Syria top the list. There are other hotbeds of perpetual conflict like Pakistan and Colombia that are also not surprising. Algeria is high on the list mainly due to the civil war that raged in the mid-90’s. Since ’96 there are only two journalists casualties in the nation.

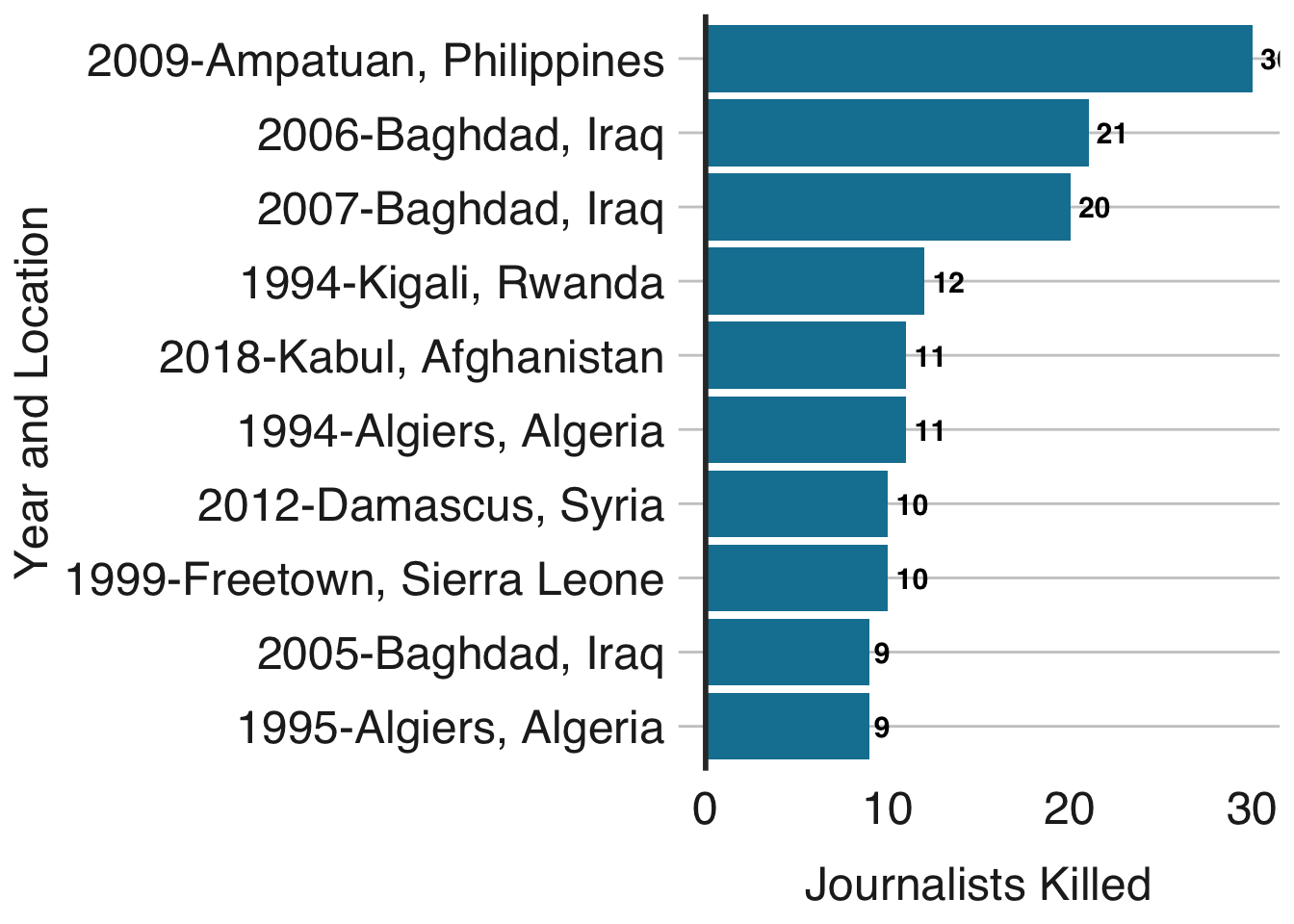

The fact the Philippines is so high on the chart amazed me, however. A look at the single deadliest events for journalists reveals why:

CPJ labels the Maguindanao Massacre as the deadliest ever event for journalists — at least 34 in total died (4 have unconfirmed motives). CPJ had apparently labeled the Philippines the second most hostile country to journalists, after Iraq, even before this massacre. The atmosphere towards free press in the Philippines remains hostile with President Duterte’s increasingly authoritarian government.

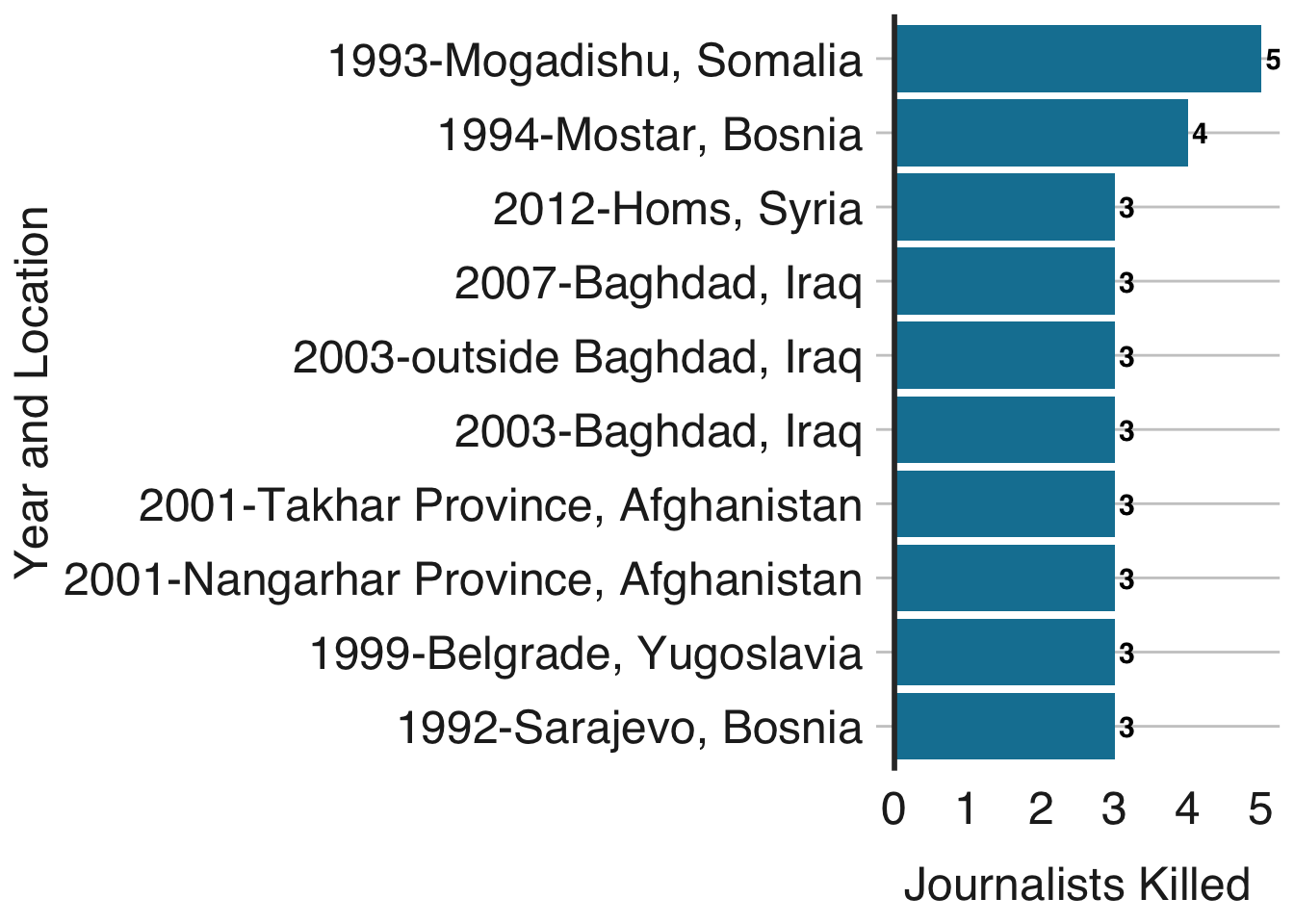

So far I looked at all journalists regardless of nationality. The CPJ data distinguishes between local and foreign journalists, so I create the same plot but for only foreign journalists:

These figures are lower than what I expected. Since the death of a foreign journalist makes bigger headlines, outsized media coverage perhaps contributed to my inflated expectation of foreign journalist casualties. I found it surprising that the deadliest event for foreign journalists occurred outside the Middle East (in Somalia) and occurred so long ago (1993). It’s also interesting to note that the wars following the dissolution of Yugoslavia have a more noticeable impact on foreign journalist casualties than more recent conflicts in the Middle East.

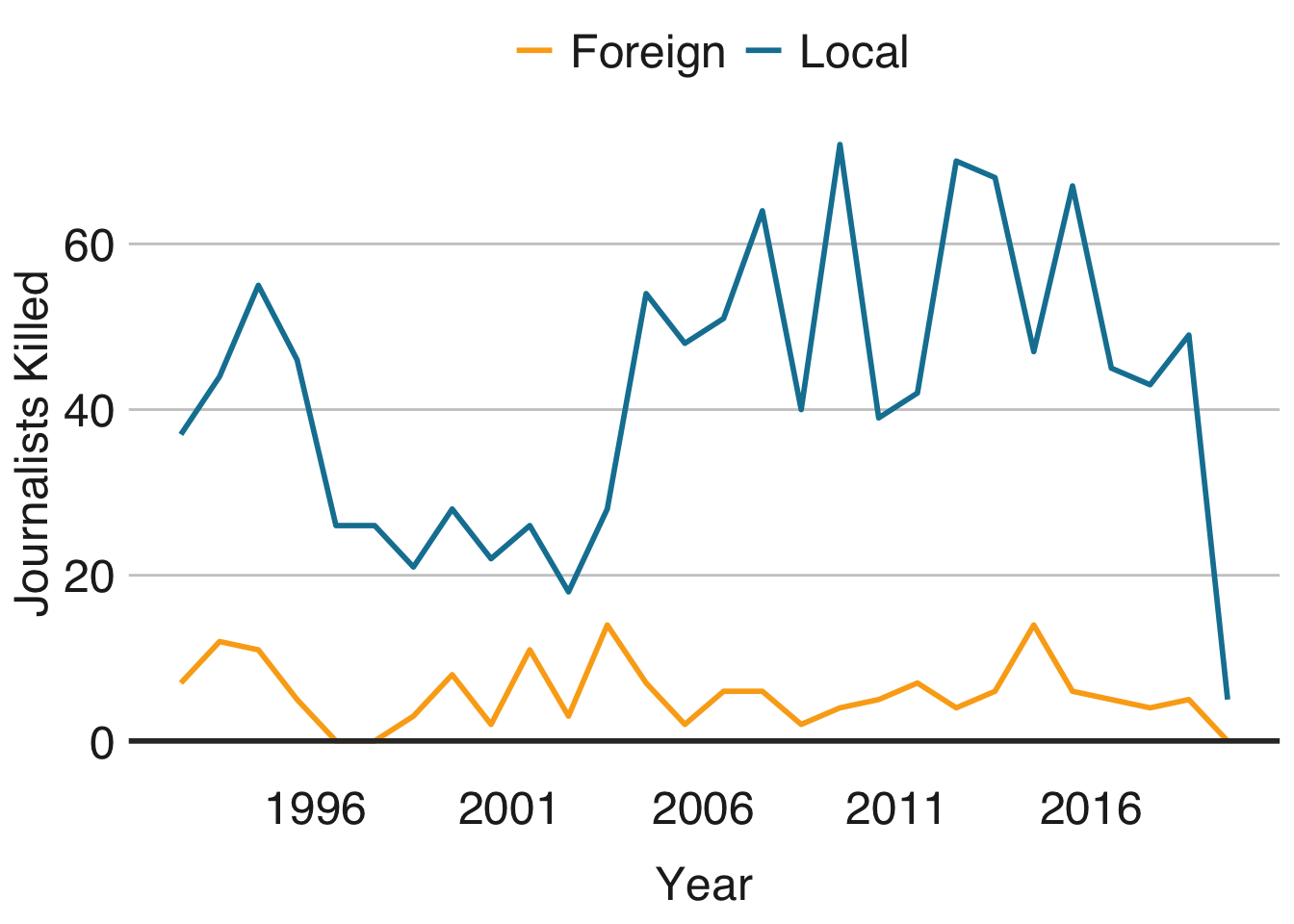

Below I compare the rates of foreign and local journalist casualties:

There are a large number of local journalist killings in the mid-90’s followed by a decline from 1996 to the early 00’s. Once the wars in Middle East begin in the early 00’s, the uptick in journalist casualties is dramatic. There is a 54% increase in local casualties from 2000 to 2001 and an astounding 100% increase between 2002 and 2003. This is the largest year over year casualty increase between any two years.

Unsurprisingly, deaths in Afghanistan account for a large number of the deaths in 2001 and deaths in Iraq account for the largest number of deaths in 2003. There was also a 51% year over year increase in journalist casualties between 2011 and 2012 coinciding with war in Syria.

Many reports I read about increasing danger for journalists do not make the distinction between local and foreign reporters. The difference is key. In the years between major conflicts from 1996 and 2001, local and foreign casualties were comparable. This changed in 2003.

Killings of local journalists soared beginning in 2003. While deaths of foreign journalists also spiked, that year marks when the magnitudes diverged vastly. Foreign casualties stayed below 10 through the 00’s while local casualties rose above 40 for most years since 2003.

Further, the killings of foreign journalists diminished in recent years. The most recent uptick for foreign journalist deaths was in 2014 caused by conflicts in Syria and Ukraine. In contrast, the casualty rate for local journalists remains as high as it was when it first climbed in the early 2000’s.

I’m curious why this discrepancy exists. There may be a higher cost to killing foreign journalists. Killing a foreign journalist risks provoking international backlash whereas the killing of a local journalist may not evoke the same response. However, one can imagine that certain terrorist groups may want to attract the media attention a murder of the foreign journalist might create.

The casualty numbers may have most to do with the total number of local and foreign journalists. There are most likely more local journalists covering local news, even during major international conflicts. When violent conflict unfolds, local journalists are closer to the action and have access to sources and stories that foreign journalists do not. Perhaps this proximity puts them in harm’s way more often than foreign journalists, which may explain the discrepancy.

At the end of the day, the distinction between local and foreign journalist is trivial. All reporters in violent conflict risk their lives to keep the world informed. It’s saddening to see that the number of reporters killed each year shows no sign of receding.