Liner Shipping Connectivity Index

Components

As part of my research with UNCTAD, I was privy to several datasets covering the world fleet that maritime economists use to analyze patterns in global shipping. One of these datasets that is particularly interesting is the Liner Shipping Connectivity Index that my research partner, Jan Hoffman, helped develop. The LSCI is a composite score of 5 separate indicators which help measure how well a country is integrated within the global container shipping network. The higher the LSCI, the bigger player a country is on the world shipping stage.

Each component metric captures a unique part of a nation’s global shipping status. The 5 components are:

Number of Ships - This is the total number of ships that provide services to and from a country’s ports.

Cargo Carrying Capacity (total TEUs) - This is the total container carrying capacity (measured in twenty-foot-equivalent units) of the ships that pass through a nation’s ports. The intent here is to measure the actual container capacity that a country can process.

Maximum Vessel Size (TEU capacity) - The size of the largest vessel in a nation’s fleet that provides services to and from a country’s port. This is an interesting component in that it intends to measure the infrastructure in a country’s ports, and not anything specific about the vessels in a country’s fleet. To accomodate large vessels, a country’s ports need to be deeply dredged and have a large and efficient crane system to offload containers. (By the way, the largest vessels in the world fleet can carry around 20,000 containers…which would require 20,000 truck drivers to transport the same load. Container shipping is efficient and green–huzzah!).

Liner Companies - This captures how many liner companies deploy container services to and from a nation’s ports in a particular year. Liner shipping is a specific type of shipping that is essential to the transhipment of containers. Liner shipping differs from “tramp trade” shipping in that liner ships have a fixed schedule of port calls, while “tramp freighters” do not have a fixed shipping schedule. To calculate this, rearchers look at the schedule of container ship port calls in all of the ports in a particular nation.

Liner Services - This refers to how many container services a country’s port system offers. We can think of a particular container service like an individual bus route in a city’s transit system. A bus route transports passengers to certain stops along a specific route, and in a similar fashion a shipping route transorts goods to certain ports on a particular route.

Clusters

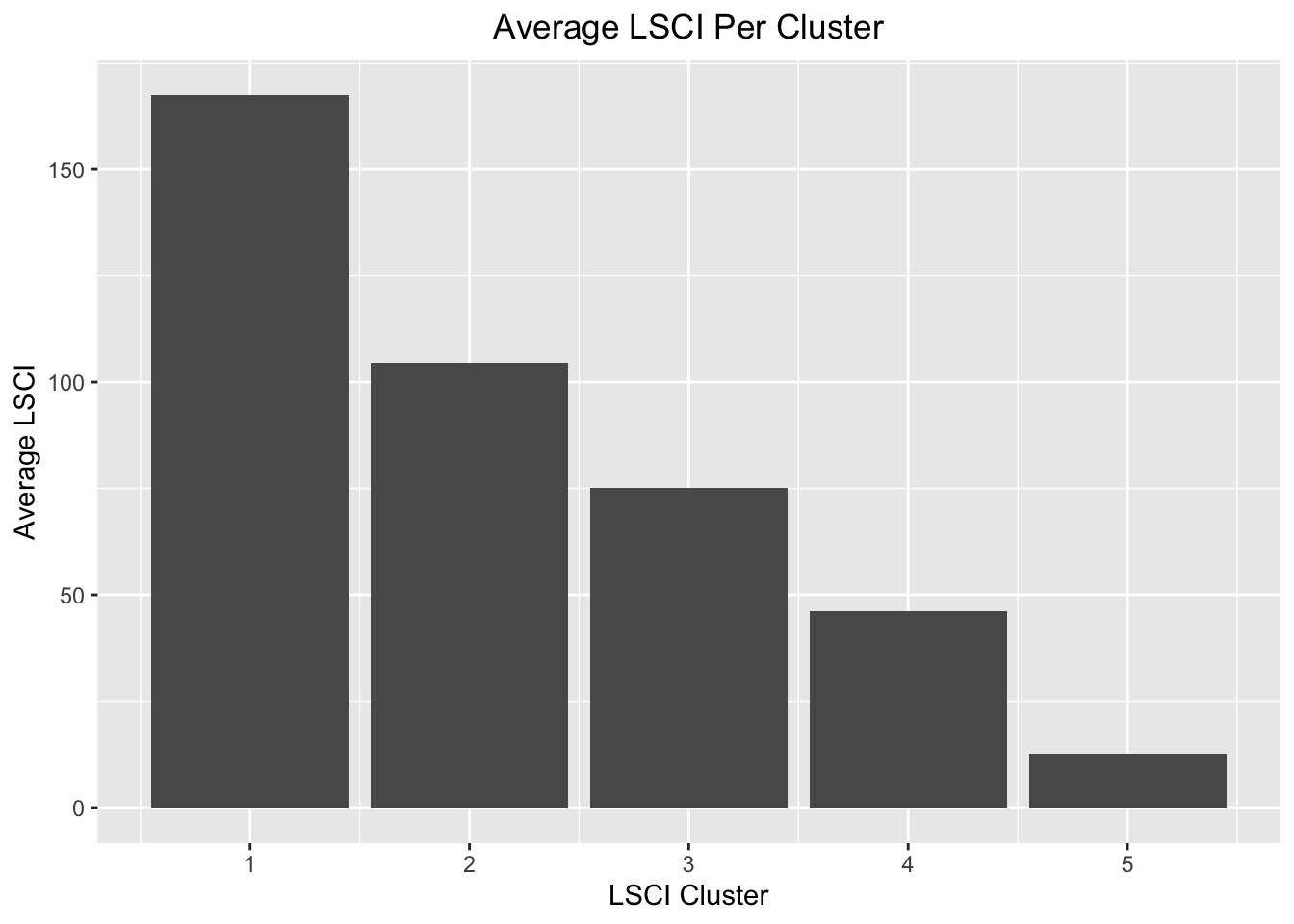

One can perform a myriad of different analyses to this dataset, but my first inclination was to cluster particular nations using all of the 5 components of the LSCI. I grouped countries into 5 different clusters using kmeans clustering, and reviewed the similarities and differences of the countries within each group. Below I plot the average LSCI for each cluster.

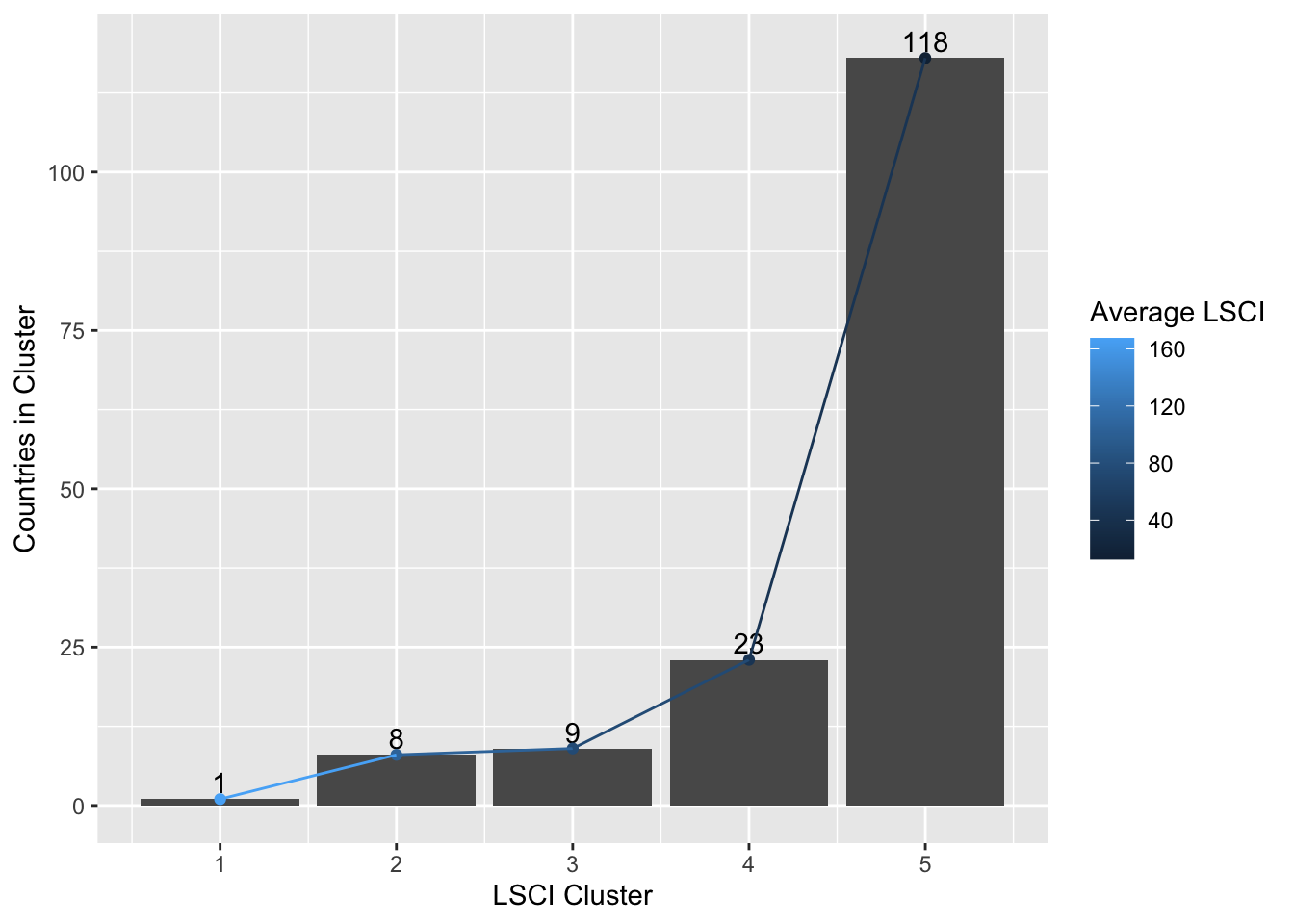

You can see that kmeans did a fairly good job of grouping countries into similar groups. The LSCI sharply decreases from cluster to cluster, meaning that countries in group 5 are the least connected countries, while those in clusters 1 and 2 are the most connected countries. Below I plot how many countries are in each cluster, as well as how the average LSCI differs in each.

It looks like there is only a single country in cluster 1, while there are 118 countries in cluster 5. The takeaway here is that well-connected countries are the exception in our global economy, and that these countries are the key drivers of the global shipping economy. Any idea what the outlier country is in cluster 1?

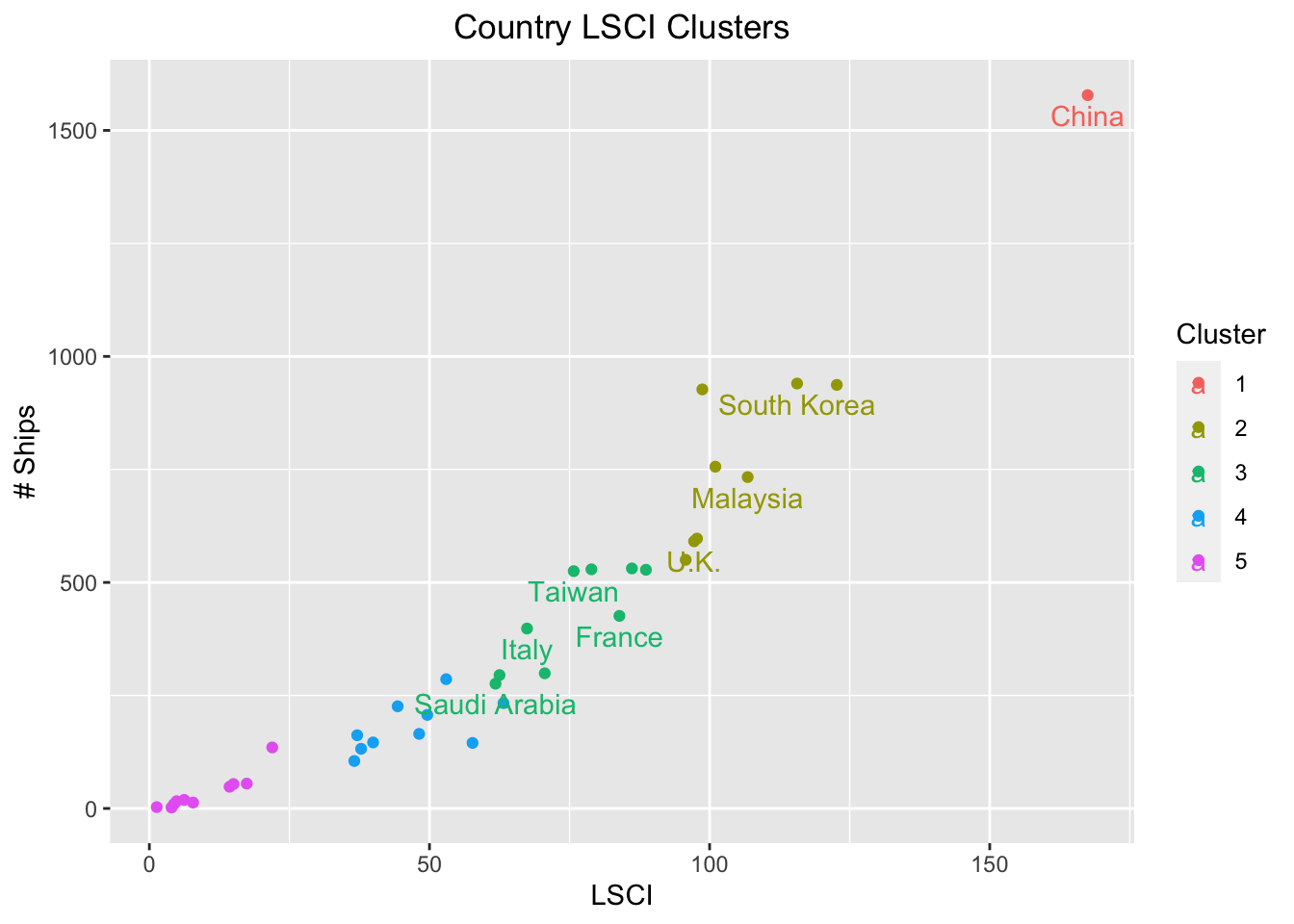

The answer, of course, is China. Since the nation surpassed Germany as the biggest exporter in 2009 and the United States as the largest trading nation in 2013, China dominates the global shipping economy, and this dominance shows up in the data. In the 2016 LSCI dataset, China leads the rest of the world in all 5 component metrics. It boasted 1578 ships, a total TEU capacity of 10,204,414, a maximum ship size with a 19224 TEU capacity, 68 liner shipping companies, and 1032 liner shipping services. The data and the plot above corroborate this fact about the global shipping world: China is in a league of its own.

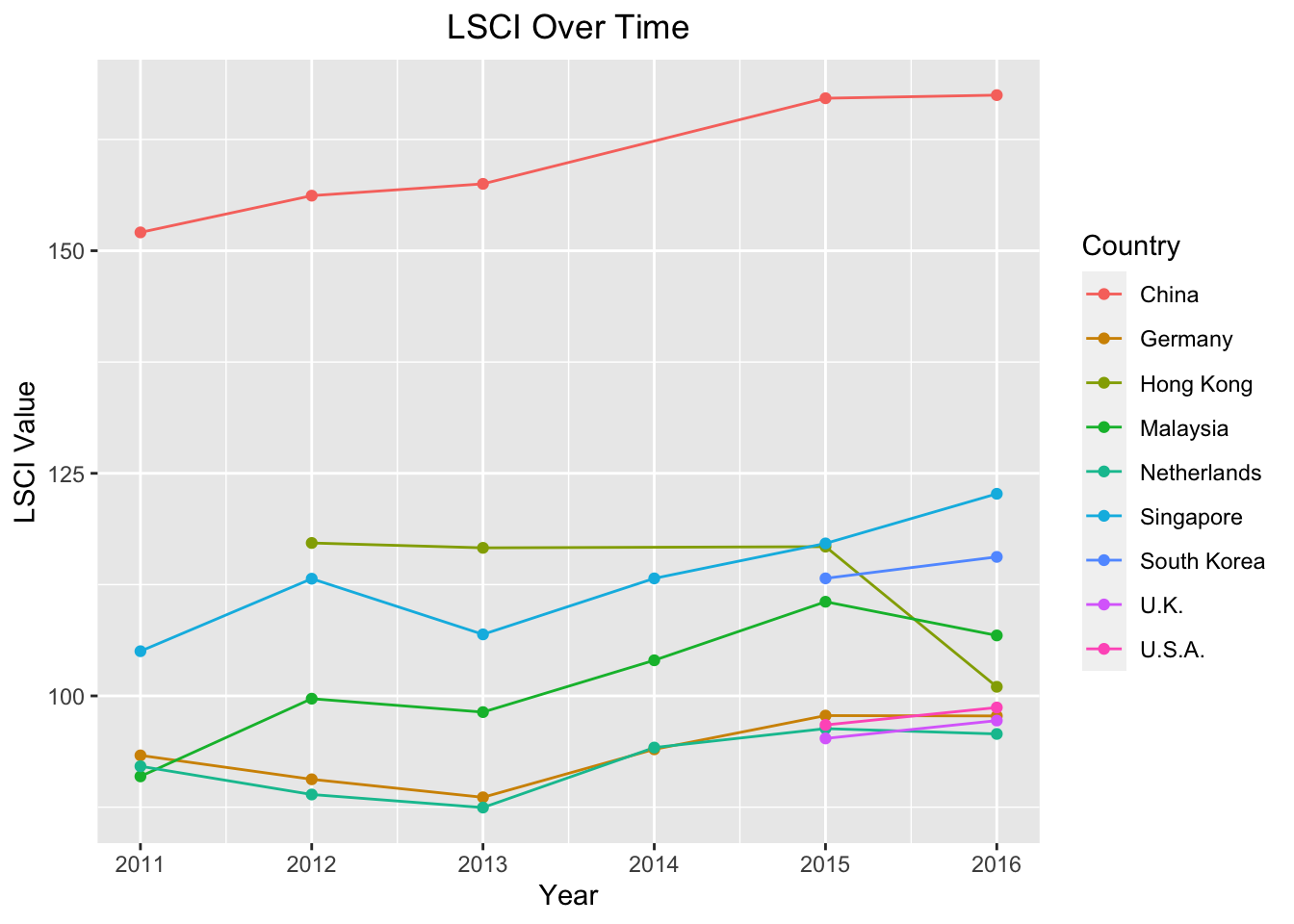

Since UNCTAD calculates LSCI each year, it is interesting to look at how the index changes over the years. Below I plot the index of the most connected countries (i.e. those in clusters 1 and 2) over each of the years that my dataset contains.

We see steady growth in China’s overall connectivity, though the growth slows in years 2015 and 2016. In contrast, we see sharp growth in Singapore between 2013 and 2016, but a sharp decline in connectivity in Malaysia in the two most recent years of data.

For those countries for which I have data in 2011 and 2016, I decided to calculate the 5-year difference in LSCI. I took the top 5 countries with the largest positive change in LSCI, as well as the top 5 countries with the largest negative change in LSCI.

Sweden has the honor of having the largest 5-year change in LSCI, while Denmark is a close second. It is encouraging also to see countries with economies on the rise–such as Poland, Colombia, and Sri Lanka–make it into the list of countries with the largest 5-year change. Speaking to Poland in particular, it is exciting that the country in recent years is embracing what maritime power it holds on the Baltic, and making due on its promises to become a global economic power.On the other hand, we can also witness in the data the negative economic effect of conflict on nations such as Venezuela and Yemen, and how this conflict impacts shipping infrastructure. However, global shipping connectivity is as much an economic measure of ties to the world economy as it is a barometer for a country’s commitment to the idea that underpins it: free trade. Taking Iran and Algeria as examples, we can catch glimpses in the data of those countries’ policy choices towards economic isolation.

Outlook

As the world economy turns toward greater globalization and we look for more cost-effective means of transporting goods across the world, we can view container shipping networks as the global economy’s nervous system. A country’s commitment to global trade–including investment in its fleet, its port infrastructure, and its policies towards open ports–determines whether or not the nation is linked to this essential global network.